With Darcy WE Allen and Jason Potts. Originally a Medium post

If we are going to realise the environmental vision of the circular economy, we need to first think of it as an entrepreneurial economy.

In PIG 05049 the artist Christien Meindertsma shows how the parts of a slaughtered pig get reused downstream. For instance, gelatine derived from the skin ends up in wine, acids from bone fat end up in paint, and pig hair ends up in fertiliser.

The farmer sells what they can to retailers and sells the rest to other businesses, who then process and resell the what they can’t use to other users and businesses, who then process and resell the other parts … anyway you get it the point.

In a world of perfect information and zero-transaction costs this use and reuse would be trivial. The near infinite uses of pig parts would be immediately apparent to everyone in the economy and every part of the pig would be reallocated efficiently.

But of course we don’t live in a world of perfect information. All these reallocations have to be discovered by entrepreneurs and innovators.

PIG 05049 is a story of how resources move through the economy in surprising ways, as entrepreneurs reduce waste in the pursuit of profit.

But a circular economy makes stronger demands on us. The circular economy aspires not simply to minimise waste, but for goods to be “reused, repaired and recycled” after their first users no longer need them.

The circular economy imagines a world in which material goods are recovered, endlessly, and thus the environmental impact of the materials that we rely on for our prosperity is radically reduced.

It’s a powerful vision. But it is a hard vision to realise because transaction costs are not zero. Obviously, as goods travel through their life cycle they deteriorate. Goods get worn out, they rust, they fall apart.

But just as critical is the fact that information about the goods deteriorates as well. Product manuals get lost. Producers go out of business. Critical parts get separated. What the goods are made from is forgotten.

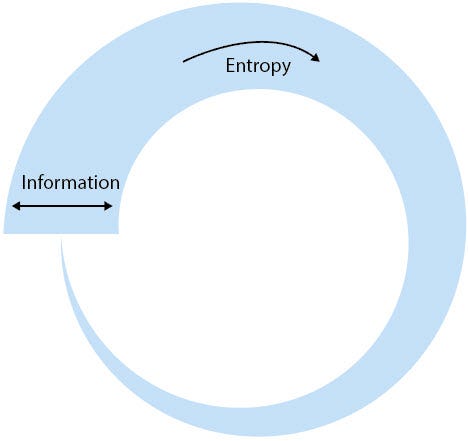

This information loss is a huge problem for the circular economy — it is very extremely expensive to reuse goods when we have lost information about what they are made of and how they work. This information entropy makes it hard for entrepreneurs and innovators to close the loop.

In some previous work we’ve described a hypothetical “perfect ledger” where information is infinitely accessible, immediately retrievable, completely immutable, perfectly correspondent to reality, and permanently available. The perfect ledger is a thought experiment. It’s a thought experiment like an economy with perfect information or zero transaction costs that allows us to see how our imperfect world differs from an imaginary ideal.

And in a world of perfect ledgers, the circular economy’s information loop is completely closed. There is no information entropy — we never forget, so we can always reuse.

Blockchain technology of course is not a perfect ledger. But on many of the relevant margins, it offers a drastically improved way of managing information about goods as they travel through their lifecycle.

Information can be stored on a distributed ledger in a way that is resistant not only to later amendment, but that persists when it a good is passed from hand to hand, or travels across a political border, or when it is discontinued and forgotten by its designer, or when its original manufacturer goes out of business.

The information about the goods we have sitting on our desk, scattered around our homes and workplaces, built into our buildings, and powering our vehicles is being unpredictably but relentlessly lost. This is the blockchain opportunity for the circular economy. Blockchains can secure more information, better, more permanently and more accessibly about goods, so that they can be more efficiently reused.

And in conjunction with similar technological developments that reduce search costs — that is, that allow innovators to identify underutilised goods in the economy that could be bought and repurposed — the owners of goods will have increased incentivises to store and protect their property, if only to maximise the sale price.

The circular economy is often thought as a problem for governments to bring about. But if the circular economy is to be realised, we need to rethink the problem of waste and reuse as an environmental problem caused by an information problem.

Technological advances in the way we store and trust information offer a vision of large-scale, yet still bottom-up environmental improvements, where market incentives, price signals and contracting work to close the industrial loop.